Securitizing Supply Chains Turns Risk into a Tradable Asset

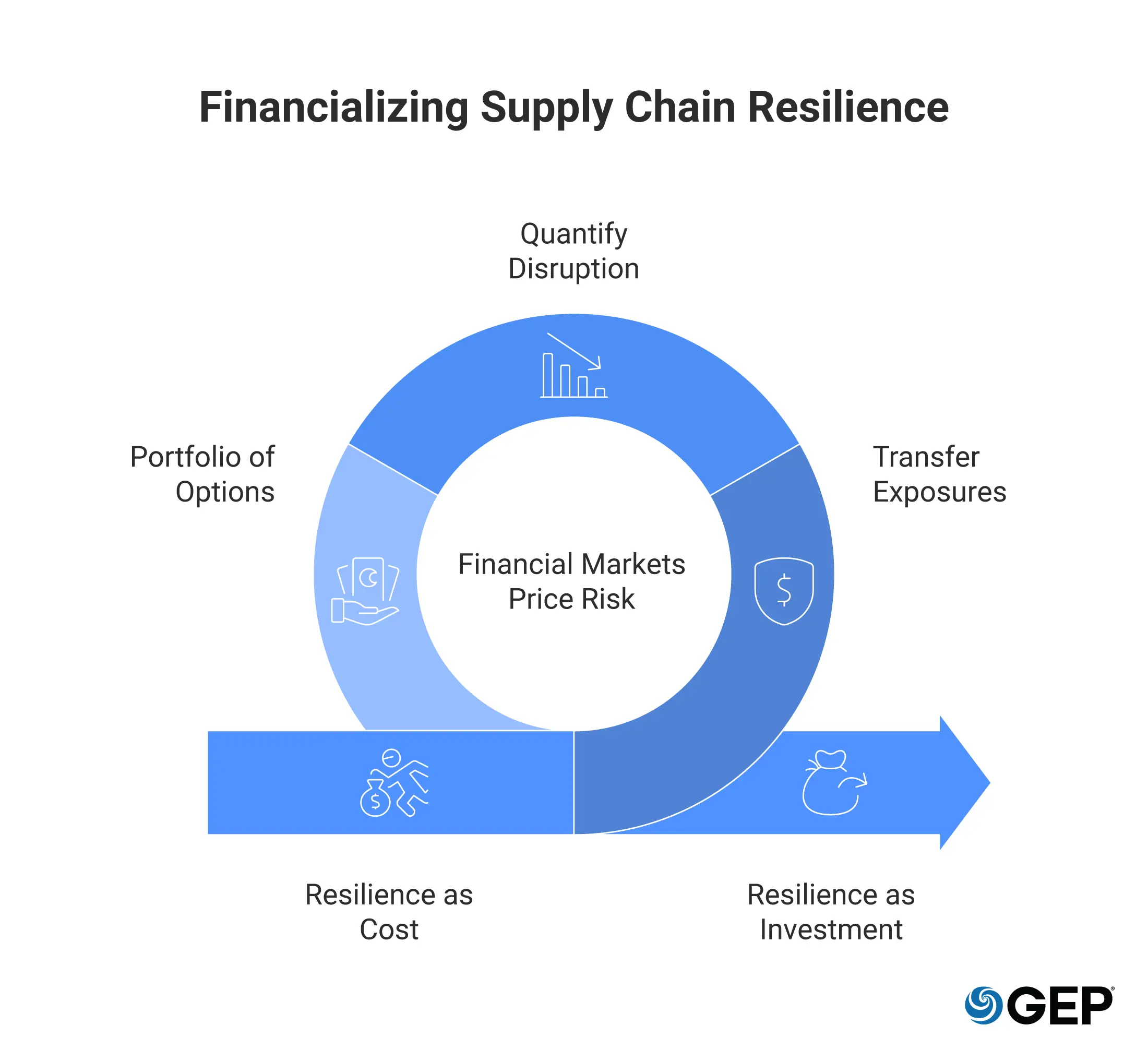

- Supply chain resilience is evolving from an operational expense to a financial asset class that allows enterprises to quantify, price and trade risk.

- By making disruption costs transparent, companies can attract external capital to fund critical infrastructure and buffer capacity.

- Success in this new era requires strict governance to manage "basis risk," the gap between market indices and a company’s actual physical exposure.

February 02, 2026 | Supply Chain Strategy 4 minutes read

For decades, the basic equation of supply chain resilience was simple: safety costs money. If a company wanted to survive a shock, whether a port strike, a supplier bankruptcy or a geopolitical flare-up, it had to pay for it up front. This meant building redundant factories that might sit idle, stockpiling inventory that tied up millions in working capital or retaining backup logistics providers at a premium.

Resilience was ultimately a drag on the balance sheet: a sunk cost necessary for insurance, but a cost nonetheless.

However, the volatility prevailing in global trade is causing a radical shift: financial markets are beginning to price supply risk directly. This evolution allows firms to transfer specific exposures to the capital markets, much like they hedge currency fluctuations or fuel prices.

But the implications go far beyond simple hedging. We are witnessing the financialization of fragility, a structural change where disruption is quantified, priced and traded. Instead of viewing resilience solely as a warehouse full of "just-in-case" inventory, forward-thinking leaders are beginning to view it as a portfolio of financial and physical options.

Pricing the Unthinkable

The prerequisite for any financial market is data. You cannot trade what you cannot measure. Historically, supply chain risks were narrated through anecdotes: "The port is congested," or "The supplier is overwhelmed." These qualitative assessments aren’t sufficient.

To unlock the capital markets, the industry is moving toward rigorous standardization. We are seeing the maturation of indices, such as the Freightos Baltic Index for container rates, which convert volatile operational costs into transparent data points. This transparency allows for the creation of financial instruments, like futures, options, and insurance-linked securities (ILS), which track these indices.

Securitizing the Supply Chain

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of this evolution is not just hedging existing risk, but how financialization can fund the infrastructure to prevent it.

Imagine a scenario where a consortium of pharmaceutical companies struggles with cold-chain warehousing capacity in a volatile region. No single company wants to spend $50 million to build a backup facility that might sit empty 80% of the time.

However, securitizing that capacity "gap" lets external investors fund the construction of the facility. In return, the pharmaceutical companies pay a fee (effectively an option premium) to reserve capacity, giving them the right to use the facility instantly in the event of a disruption.

The investors get a steady, bond-like yield from the reservation fees. The companies get guaranteed resilience without the massive capital expenditure (CAPEX) on their books. This is how the financialization of risk protects margins while simultaneously attracting capital to the weak points of the global supply chain.

Discover More: Supply Chain Resilience

The CFO’s New Lens: Risk-Adjusted Returns

This evolution alters the relationship between Chief Supply Chain Officers (CSCOs) and CFOs.

For years, CSCOs have been asking for budget increases to fund buffers. CFOs, tasked with optimizing working capital, often view these requests as inefficiencies. "Why do we need 90 days of inventory when our forecast says we only need 45?"

Financialization changes the language of this negotiation. The CSCO is no longer asking for "safety stock." They are presenting a risk management strategy with a clear cost-to-coverage ratio.

They can now say: "We have an exposure of $100 million if this trade lane shuts down. We can cover 60% of that exposure through physical inventory, which costs us $2 million in holding costs. We can cover the remaining 40% through a freight hedge that costs $500,000 annually. This blend minimizes our capital outlay while maximizing our coverage."

This is the language of risk-adjusted returns. It allows the CFO to evaluate resilience as a strategic investment rather than a bloated expense. It brings the supply chain conversation out of the warehouse and into the treasury.

Your Tariff Impact Playbook Is Here

How to Evaluate Tariff Exposure, Control Spend and Reduce Risk

The Governance Challenge: Managing the Imperfect Hedge

While the promise of securitization is immense, the risks of mismanagement are equally high. Writing a check for an insurance policy is simple; managing a portfolio of financial hedges is complex.

The GEP Outlook 2026 report identifies "basis risk" as a critical hurdle. Basis risk is the mismatch between the financial instrument and the actual physical exposure. Because of that mismatch, governance must evolve alongside these new tools. A company cannot simply start trading futures without rigorous controls. This requires:

• Clear Trading Authority

strict definitions of who is authorized to execute trades and at what volume.

• Segregation of Duties

Ensuring the team measuring the risk is not the same team executing the trade.

• Independent Audits

Regular reviews to ensure the financial instruments are truly offsetting physical risk and not drifting into speculation.

Boards of directors will need to be vigilant. The goal of supply chain securitization is to stabilize the budget, not to turn the procurement department into a profit center for speculative trading.

A New Language for Leadership

Operational excellence isn’t going anywhere. No financial derivative can offload a container stuck on a vessel, and no futures contract can manufacture a microchip during a shortage. Physical agility remains the bedrock of operations.

However, financial instruments can buy what is most valuable in a crisis: time and predictability. By blending physical buffers with financial hedges, companies can smooth out the volatility in global trade.

Supply chain securitization is just one of the critical themes reshaping the global business landscape. To stay ahead of the curve, leaders need a comprehensive view of the trends defining the next era of procurement and supply chain management.

Dive deeper into the strategies that will define leadership in the coming years. Read the full GEP Outlook 2026 Report here.